There’s one thing that is common to every single business out there: accounting. Granted, the kind of accounting that goes on in a single member small business may be vastly more informal and less detailed than that of a large public company, but both “do accounting,” or at least have someone do it for them. Even though accounting is often unrelated to most business operations, we can’t escape the fact that accounting is a necessary component of running a business.

So instead of leaving you to avoid financial recordkeeping and do it begrudgingly, this article thread aims to explain the purpose accounting serves and teach you how you can save costs by doing it yourself.

Part 1: The Purpose of Accounting

Financial accounting is essentially the practice of keeping a record of a company’s transactions, analyzing those records, and presenting them to interested parties to aid them in decision making. Accounting has been around since ancient Mesopotamia, highlighting its necessity within any society whose citizens engage in trade. Since then, accounting has evolved to the “double-entry” system we use today and continues to be both a necessary and beneficial facet of business.

1) Accounting is necessary for providing government mandated reporting.

This is the foundational reason every business needs accounting. Even if you couldn’t care less about seeing your financial information and would be content with simply knowing your bank account balance/s, you’ll need more detailed information to adequately file taxes. What tax forms you must file depends on your business structure, but every business must file relatively detailed financial data. For instance, sole proprietors must attach a Schedule C (Form 1040; https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f1040sc.pdf) to their individual income tax returns, which requires the filer to offer amounts specific to a variety of expenses incurred by their business that year and to offer highly detailed information regarding their Cost of Goods Sold expense (I’ll explain CoGS in a later article in the thread).

Partnerships must file Form 1065 (https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f1065.pdf), reporting partnership income. This form is even more extensive than Schedule C (Form 1040) for sole proprietors, requiring partners to present their BOY (beginning of year) and EOY (end of year) balance sheets, among other things.

Similarly, corporations must file Form 1120 (https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f1120.pdf) with balance sheet data and more. So regardless of how your business is structured, you’ll be required to provide specific financial information that is a major pain (not to mention inaccurate) without accounting records.

NOTE: while beyond the scope of most companies, businesses that “go public” by issuing their shares to the public in an IPO (initial public offering) are also required to file incredibly detailed, audited (independently tested to be free of material misstatements), financial statements with the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission), which are available to the public (https://www.sec.gov/edgar.shtml).

2) Accounting can help you make better business decisions.

The classic expression is that accounting is the language of business, meaning that the record keeping involved effectively communicates a company’s position at any given moment, as well as documents past events/trends and change. In fact, even just an income statement and balance sheet, taking no more than a few pages, can give an incredible amount of information about your business. Accounting is ultimately to aid decision makers in making decisions, and there are no more important decision makers to a business than its owners and employees. We’ll dig deeper into this concept later, but for now know that accounting can provide valuable insights that enable more successful business.

3) Accounting can make life easier by clearly delineating expenses and saving the time it takes to backtrack later.

For small business owners, separating business and personal expenses can be a challenge, especially without business accounting. Having a system for recording and separating business expenses can be quite valuable and save you from headache. Also, timely entry of transactions saves the business owner from having to periodically backtrack to enter expenses, guess at what spending was for, and potentially even forget to record deductible expenses that would have saved money on taxes.

Now you know a little bit more about why businesses, including yours, need accounting, and how it can benefit you. Accounting is meant to help your business, not inconvenience you. If your business has the money and doesn’t want to deal with it, by all means outsource. However, if you want to save on costs and are up for a challenge, you can learn how to perform the accounting functions for your business and turn that former hassle into a tool that benefits you.

Part 2: How to Set Up Accounting To Do on Your Own

If you want to save money for your business and perform your own accounting functions, but don’t know how to, this is for you!

To get started doing your accounting, you’ll need to make some key decisions as to what methods you’re going to use, secure an accounting system to help you do the job, and establish your company’s accounting framework. Let’s walk through what all that means.

Initial Method Decisions

The first decision you’ll need to make, when doing your own accounting, is whether you’re going to use the Cash or Accrual method. What you decide will bear huge ramifications on how you account for your company's economic activity, and you’ll be required to indicate what you chose on your tax forms (e.g. Item F on Schedule C of Form 1040).

Yes, technically you can use a hybrid method, but it’ll be much easier for you to begin with either Cash or Accrual unless you have an accounting background.

So, what are the Cash and Accrual accounting methods? Both aim to record transactions but differ in the timing of when certain transactions are recorded. As you might expect given its name, the Cash method involves recording journal entries only when cash actually changes hands (e.g. when you receive cash from a customer). In contrast, the Accrual method requires a journal entry to be recorded every time a revenue or expense is incurred. Let me illustrate this difference with an example:

- Event: Bikes, Inc. has maintenance done on their shop. They don’t pay that day but receive an invoice with payment terms.

- Cash Method Treatment: No cash has changed hands, so there’s no entry.

- Accrual Method Treatment: Because an expense was incurred, Bikes, Inc. records an expense. The other end of the entry is Accounts Payable, a liability account that lets them know they owe the maintenance company for the expense. When Bikes, Inc. pays the invoice, they record another entry that reflects the decrease in Accounts Payable and the outflow of cash.

While you’re allowed to choose either method, it’s recommended that you opt to use the Accrual method unless you have a very simple business with few and infrequent transactions. Accrual provides a more accurate picture of what’s happening in your company.

Note: If your business relies on inventory you may have to use Accrual.

Another decision you’ll have to make is what method you’re going to use to value inventory at year end (for reporting). The options are “Cost,” “Lower of Cost or Market,” or “Other” (which requires additional consideration). The Cost method involves recording the total value of your inventory at year end in terms of how much you paid for all of it. The “Lower of Cost or Market” method, as the name implies, requires you to determine (if readily determinable) what the current market value of your inventory is at year end, and record the total value of all inventory based on the lower value of each inventory unit’s historical cost and market value. You may choose either method, but certainly rely on the Cost method if determining the current market value of your inventory would prove challenging.

Note: There is an exception for Small Business taxpayers, who are allowed to ignore inventory tracking and instead flow products through a supplies and materials type account (see IRS instructions at https://www.irs.gov/instructions/i1040sc).

Choose an Accounting System

Now that you’ve made a few of the important upfront choices, you’re ready to choose an accounting system. While accounting can be quite detailed and meticulous, accounting software usually automates as much as possible and simplifies the process for you. What you choose depends on a number of factors:

- Desktop vs. Web/Cloud

Some software is downloaded and hosted locally on your computer, while other applications are hosted on the cloud and can be accessed wherever you have an internet connection. Sometimes the pricing model of a system is related to the platform, with desktop tending to involve an upfront cost and cloud software an ongoing subscription.

- Your Budget

Thankfully, there are a wide variety of accounting packages on the market, giving you a large range of options to choose from. There are free accounting solutions available (e.g. open source) all the way up to expensive enterprise suites with state of the art functionality.

- Familiarity & Width of Adoption

The more people use a particular software, the more help articles, specifically tailored solutions, and more there tend to be related to it. QuickBooks is practically a household name when it comes to accounting, and you’ll certainly be able to find a much larger number of people who are familiar with it and can offer platform specific guidance if needed. Of course, choosing a widely adopted system isn’t a necessity, it just depends on your comfort level.

- Functionality

The functionality of your accounting software is arguably the most important factor. You need a system that can meet your needs. Thankfully, just about every single solution you could choose will have the basics necessary for accounting. Differentiation instead usually involves features like credit card expense tracking and tax integration, which are useful but not necessary to doing your job.

There are some things to think about to get you started. Shop around and find the platform that best meets your needs!

Establish Your Accounting Framework

The first thing to do in setting up your accounting system, beyond introductory and logistical steps like setting your name, fiscal year timeline, etc., is building a chart of accounts. Your organization’s chart of accounts will serve as the index for all the individual line items that your accounting will track. Your system will likely come preloaded with some basic ones like Cash (an asset account), Retained Earnings (an Equity account), etc. How you build the rest of them will depend on what level of detail you want to capture about your business. For instance, I could theoretically have one Expense account that every single expense touched. Reporting would show one line with a total of all business expenses, but nothing else. Or I could use more expense accounts (like utilities expense, rent expense, supplies expense, maintenance expense) to capture more detail, offering separate line items in reporting that give detail as to amounts paid for various categories. It’s recommended that you don’t be too broad in defining your chart of accounts, but you’ll also want to avoid being too detailed. You could potentially have a different expense account related to every single expense you make, but that would be a nightmare. Instead, your goal should be to have enough accounts to capture a level of detail that would be informative and insightful, while also keeping the process of deciding which account a transaction applies to simple. Think through what that means for your business, or even look for a template that you can fine tune and use for yourself.

Beyond establishing a chart of accounts, accounting system setup involves creating (or ideally, importing) customer and vendor accounts. Called subsidiary accounts, customer and vendor accounts will allow you to track data specific to individual customers or vendors but won’t appear in your chart of accounts or financial statements. These can be incredibly useful for things like answering customer questions and monitoring B2B relationships.

If your business has already been running, you’ll need to enter starting balances (which most systems provide the opportunity to do). Once that’s done, you’re all set and ready for performing your business’ accounting functions on your own!

Part 3: Doing Your Accounting on Your Own

Now that you understand the purpose of accounting and have chosen a system to use and imported starting details (not sounding familiar, go back and read (article link) and (article link) and then come back here), you can begin accounting! Here we’ll look at what you’ll be doing on a regular basis, and what significant events take place in the accounting cycle.

The process of accounting generally involves the following steps:

- Record journal entries.

- Post journal entries to the appropriate ledgers.

- Prepare a general ledger trial balance.

- Make adjusting entries.

- Use the updated general ledger trial balance to prepare financial statements.

- Make closing entries.

Now, let’s walk through this process to understand what’s happening at each step on the way.

Record Journal Entries

Recording journal entries is really the bulk of the work when it comes to accounting. If we could divide the steps above according to how much time is spent performing each one, step #1 would far exceed the rest. That’s because steps 3-6 only happen at year end (or at whatever frequency you prepare financial statements) and recording journal entries is done on a regular basis throughout the year. In fact, journal entries need to be recorded every time there is an economic transaction, which happens quite frequently.

To understand journal entries and how to record them, you need to understand the accounting equation.

What this equation does is mathematically illustrate that everything you have (assets), you have either because you have borrowed it and owe some obligation (liabilities), or because you have earned it (equity). Every single journal entry we ever record MUST fit this equation (more on that in a moment). This is the fundamental logic behind the double-entry accounting system, and the fundamental mechanism is the journal entry, with debits and credits touching different accounts. It’s with journal entries that we make records of things like our assets going up or our liabilities going down. They are the vehicle used to capture transactions and what they mean for us. But how do we know what accounts should be included in an entry, and which should be debited vs. credited?

Recall from the previous article in this thread that accounting systems require something called a Chart of Accounts. These general accounts are designed to capture the appropriate level of detail for your business, and can fall into the larger categories of asset, liability, equity, income, or expense accounts. These account categories are derived from the accounting equation. But wait, you might be asking, where are the income and expense accounts in the accounting equation? Good question. Remember that Owner’s Equity is used to explain what we’ve earned. Well, there is an account found in any chart of accounts called something like “Retained Earnings” or “Capital,” which essentially captures income and expenses. Notice that the accounting equation is able to tell you a lot about your financial position at any given moment (e.g. what do I have right now, what do I owe right now), but is not able to as clearly give details on financial performance over time (e.g. what was my net income over the last six months). To show time-series information like that, we use the temporary accounts income/revenue and expenses. These accounts are considered temporary because we close them at each year end, and they begin each year with a zero balance. To finally come full circle, we close these income and expense (and dividend) account balances to Retained Earnings, so that our total equity essentially changes the amount of net income (loss; not including the effect of dividends). So, even entries involving income and expenses balance the accounting equation (e.g. you pay me for my product, I debit cash so an asset goes up, and I credit income, which flows through to equity, and my equity goes up the same amount).

Each of these major categories of accounts behaves predictably according to rules that dictate what kind of entry (debit or credit) makes the account balance increase or decrease. Before explaining those rules, allow me to make it clear that, for accounting purposes, the words debit and credit have nothing to do with debit and credit cards used in traditional finance. Now, how do you know which accounts rise with a debit and which with a credit?

“DC ADELER” is a helpful tool to remember which types of accounts rise with debits and which with credits. The DC stands for “Debit” and “Credit,” at the top of the t-account mockup (the horizontal line with a perpendicular vertical line beneath it; t-accounts are a helpful tool for visualizing accounts and their balances). The ADE part of ADELER belongs on the left under debit and shows accounts that rise with a debit: Asset, Dividend, and Expense accounts. Conversely, the LER part of ADELER belongs on the right under credit and shows the accounts that rise with a credit: Liability, Equity, and Revenue. So, every time an asset account (like cash) is debited in a journal entry, the associated account balance goes up, and every time a revenue/income account is credited, that associated account balance goes up. You need to know also that all types of accounts can be both debited and credited; debiting some accounts will always make them increase, but for other accounts a debit will make them decrease, and the same is true for credits. For instance, let’s say I am paying off a loan, I would debit the liability account for that loan, which would make the balance in that account decrease (reflecting the fact that I don’t owe as much). The other side of that entry would be a credit to cash (an asset account), which would decrease its account balance (to reflect me having less cash). Just remember, any account can be debited and credited, and whether the balance will go up or down for any given account depends on the rules for that account category. Try to remember DC ADELER, which tells you what entries make what accounts go up, and then just make the opposite entry (debit vs. credit) of that when you need an account balance to go down. Also, treat any contra-accounts you might run into in the future (e.g. accumulated depreciation, sales returns) the opposite that you would the account type it runs contra to (e.g. credit a contra-asset to increase the account balance).

Now that you know more about how we’ll determine what to debit and what to credit, let’s practice a little bit with a few scenarios. Each journal entry must involve at least two lines (hence, the double-entry system), have equal total debits and total credits, and also balance the accounting equation (assets = liabilities + Equity). What would the journal entry be in the following scenarios (assume accrual method)?

- You pay the monthly rent bill for your store with cash.

Note: even though an expense does involve money going out of your hands, the purpose of an expense account is to track the total amount paid for a given type of expense. So, in this example we allow the credit to cash to tell our system that we have less money now, and debit our rent expense account to increase that account balance. If we were to look at the ledger for that account, it would tell us the total of how much we’ve paid in rent for the year.

- You receive a loan for $10,000 from the bank.

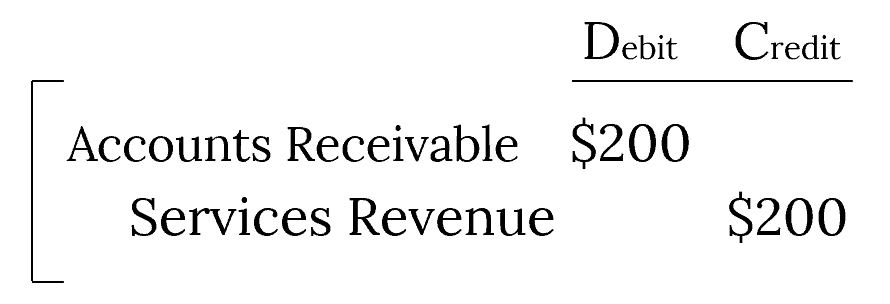

- You invoice a customer for services you provided them worth $200 that they have yet to pay for.

Note: remember that with accrual accounting we record entries even when a revenue/expense is incurred or earned, even if cash doesn’t change hands. In this case we debit Accounts Receivable, which is an asset account that rises with a debit and reflects the fact that someone owes us money. Because we already performed the service, we can record revenue.

- You pay $3,000 cash in advance of your next few months’ utility bill.

Note: we did pay cash, so we want to credit that to decrease its account balance. But again, we only record revenue and expenses when incurred, and this expense hasn’t been incurred yet. So instead of debiting our utilities expense account, we need something else. What we have here is an asset, because instead of having to pay out of cash later we’ll be able to simply deplete our advanced payment. So, we debit prepaid expense, which is an asset. Now for a more challenging example…

- You receive $20 cash for an inventory item that originally cost you $13.

Note: hopefully you were able to recognize that we need to debit cash because we’re receiving money and credit a revenue account (product sales) because we earned income. What you may not have known is that, upon sale of inventory, we also need to record the expense associated with that item. When we purchase inventory, instead of debiting an expense, we debit an asset account called Inventory, which tracks the value (usually at purchase cost) of our inventory. We did pay for that, however, and need to eventually reflect that money was spent by debiting an expense. With inventory, we recognize that expense at the time we sell it. The Cost of Goods Sold account is an expense account (pretty much the only expense account that doesn’t have “expense” in its name) tied to inventory. In this example, we write off the product’s value in inventory (asset account) because we no longer have it, and finally record the expense related to purchasing it. If you were to look at all the entries related to that one item, you’d see that the net effect was a cash inflow of $7 and income of $7 (revenue of $20 minus expense of $13); inventory zeros out.

How did that practice go? If that was easy for you, then you’re well on your way to being a great accountant! If it was a struggle and you had to wait for the explanations, don’t be discouraged. Learning accounting takes effort. Just keep practicing by imagining all sorts of different kinds of transactions you might face and thinking through how you would account for them. There are also a plethora of resources available online to help you continue to learn and practice. Make sure you understand the purpose and mechanics of capital assets and associated depreciation and accumulated depreciation, different methods related to inventory accounting (e.g. FIFO vs. LIFO), and how to handle whatever unique accounting situations might arise in your industry. Don’t worry, just like recording journal entries is by far the most time intensive part of accounting, this was by far the longest section in the article.

Post Journal Entries to Ledgers

Thankfully, most accounting systems will perform this step for you automatically when you save a journal entry. Still, for your understanding here’s a brief word on this step. Before the time of computers, accounting had to be done by hand. That being the circumstance, it wasn’t enough to simply write down a journal entry somewhere, because that would do nothing to change the balance of the relevant accounts. Instead, accountants would have to take the information from a journal entry and post it to accounts. For instance, if my journal entry involves a debit to cash, then I would need to go to the Cash account ledger (where all transaction history- all debits and credits- for cash are stored) and write the debit there and update the balance in the Cash account. I’d do the same for whatever account was credited. That way account balances are perpetually caught up to the journal and are accurate. If you’re using a pen and paper or archaic software system for your accounting, you’ll need to learn how to do this. Otherwise know that every time you record a journal entry, your accounting software is posting the debits and credits to the associated accounts automatically and updates the account balances.

Prepare a General Ledger (GL) Trial Balance

Each of the following steps, including this one, take place at year end or whenever financial statements are prepared. As you pass the end of your fiscal year, the first step in preparing to close out one year, analyze it via the financial statements, and launch into the next, is to pull a GL trial balance from your accounting system. A General Ledger (GL) Trial Balance is nothing more than a sheet that lists each of the accounts in your chart of accounts (or at least those with a non-zero balance) and the balance as of a particular date. Viewing this document, which your system should be able to produce rather easily for you, will alert you to any potential errors that might have been made during the year and inform you of what other adjusting entries may need to be made.

Make Adjusting Entries

Many companies record depreciation only once yearly, and they do so at year-end. To do so, they record a journal entry that debits depreciation expense for the year and credits the associated accumulated depreciation accounts. This is an example of what kinds of things may be included in year-end adjusting entries. The goal of an adjusting entry is to “right the ship,” if you will, or make the necessary records that haven’t been made yet and correct any errors or misclassifications that occurred during the year so that the records will be accurate and ready to be used in generating financial statements.

Use the Updated GL Trial Balance to Generate Financial Statements

Many systems allow you to generate financial statements simply by clicking a few buttons and watching them do the rest. Know that what financial statements you choose to generate depends completely on what you and other interested parties (e.g. board, stakeholders) want to know; this step isn’t even technically a requirement at all, though it can be helpful at least in filing your taxes. Here are common financial statements for you to consider:

- Balance Sheet: like the trial balance but without income or expense accounts, the balance sheet gives the account balances for asset, liability, and equity accounts as of the last day of the fiscal year. Total assets = total liabilities + owner’s equity.

- Income Statement: unlike the balance sheet, the income statement revolves around the income and expense accounts, showing you income and expense information from the entire year, culminating in a bottom-line net income number.

- Statement of Owner’s Equity: most used by public companies or those with at least semi-complicated ownership structure, this statement details changes in equity for the year, such as issuance of common stock and dividends.

- Statement of Cash Flows: this statement works, as its name implies, to detail the actual cash flows that occurred during the year, dividing them into the categories of operating, financing, and investing.

- Cash on Hand: a relatively simple statement, cash on hand may be used to detail the bank accounts owned by the company and their balances as of the last day of the fiscal year.

There are other kinds of financial statements, so if you need something in particular that isn’t satisfied by one of those, keep searching!

Make Closing Entries

Ah, the last step in the accounting cycle. Once again, most accounting systems will do this for you, so that you don’t technically even need to be aware that it’s happening. Still, it’s valuable to understand. Remember that we have temporary accounts, income and revenue, and permanent accounts, assets, liabilities, and equity? Well, here’s where that distinction really shines. The last entry of the fiscal year will close all your income, expense, and dividend accounts to Retained Earnings (or whatever else you call it). If you had to do it yourself, this would look like debiting all of the income accounts and crediting all of the expense or dividend accounts for the total balance of what is in those accounts at the time (to bring the balances back to zero), and hitting Retained Earnings with the difference (a credit if you had net income and a debit if you had net loss). Thankfully, though, you most likely won’t have to do it yourself and can just sit back, relax, and watch as your temporary accounts are automatically closed and made ready for the start of a new year.

Conclusion

Congratulations, you now have a decent understanding of what’s happening in the accounting process and are on your way to DIY accounting. Thanks for joining me through this thread, and happy accounting!